The Next Wave in Reading Technology

Marjorie Jordan and Kathy Crowley

Summary

It is widely accepted that reading is one of the most efficient ways to acquire information; better readers are more confident and have more educational, career, and life opportunities. Many people in the United States can read, yet, the US Department of Education finds that most are not proficient. There are countless individuals not fully participating in the knowledge economy. It is not just basic literacy that is important; proficient reading has a broad-reaching societal impact.

It is widely accepted that reading is one of the most efficient ways to acquire information; better readers are more confident and have more educational, career, and life opportunities. Many people in the United States can read, yet, the US Department of Education finds that most are not proficient. There are countless individuals not fully participating in the knowledge economy. It is not just basic literacy that is important; proficient reading has a broad-reaching societal impact.

Reading material delivered in a one-format-fits-all model has been the norm for centuries on paper and for decades electronically. Yet, research demonstrates strong readers and struggling readers, adults and children, all have the potential to experience improved reading outcomes using a technology-enabled model of reading with personalized text formats. We posit that technology affordances create new opportunities; rather than optimize for the population, we can optimize reading formats for the individual. We recognize Adobe’s innovative work to enable readers to reflow and reformat PDFs to support improved reading outcomes.

We use Clayton Christensen’s frameworks to describe how the approaching wave of reading technology will address customer’s next-generation performance needs, therefore expanding the written material market to currently underserved and unserved customers. The convergence of increasingly ubiquitous technology, digital content, and reading applications make it possible to imagine a world of personalized reading formats, significantly improving reading proficiency and comprehension, making each reader the best reader they can be.

Introduction

Generally, people in the United States can read. But individual differences in reading proficiency are so significant that the US Department of Education finds that only 13% of adults[1] and 34-37% of children[2] are proficient readers. These statistics indicate a much bigger issue; educational systems typically do not qualify most of these non-proficient readers for specialized assistance. There are countless underserved and unserved individuals not fully participating in the knowledge economy. Adults and children alike create strategies to avoid reading, make mistakes at school and at work, and miss important information. It is not just basic literacy that is important; proficient reading has a broad-reaching societal impact.

The sharp rise in technology distribution and adoption in 2020 for both students and knowledge workers creates an opportunity to improve reading experiences. The expansion of technology usage has produced ever-increasing demands for literacy. To participate in their games and social structures, children must read at an early age. Literacy experts Vaca et al. note, “Adolescents entering the adult world in the 21st century are expected to read and write more than at any other time in human history. They will need advanced levels of literacy to perform their jobs, run their households, act as citizens, and conduct their personal lives.”[3] When we invest in raising individual reading performance, everyone benefits.

The sharp rise in technology distribution and adoption in 2020 for both students and knowledge workers creates an opportunity to improve reading experiences. The expansion of technology usage has produced ever-increasing demands for literacy. To participate in their games and social structures, children must read at an early age. Literacy experts Vaca et al. note, “Adolescents entering the adult world in the 21st century are expected to read and write more than at any other time in human history. They will need advanced levels of literacy to perform their jobs, run their households, act as citizens, and conduct their personal lives.”[3] When we invest in raising individual reading performance, everyone benefits.

Reading material delivered in a one-format-fits-all model has been the norm for centuries on paper and for decades electronically, creating this milieu of non-proficient reading. We posit that technology affordances create new opportunities; rather than optimize for the population, we can optimize reading formats for the individual.

Figure 1: What is Readability, and Does it Matter? (2021, February 16). Readability Matters. https://readabilitymatters.org/articles/what-is-readability-and-does-it-matter

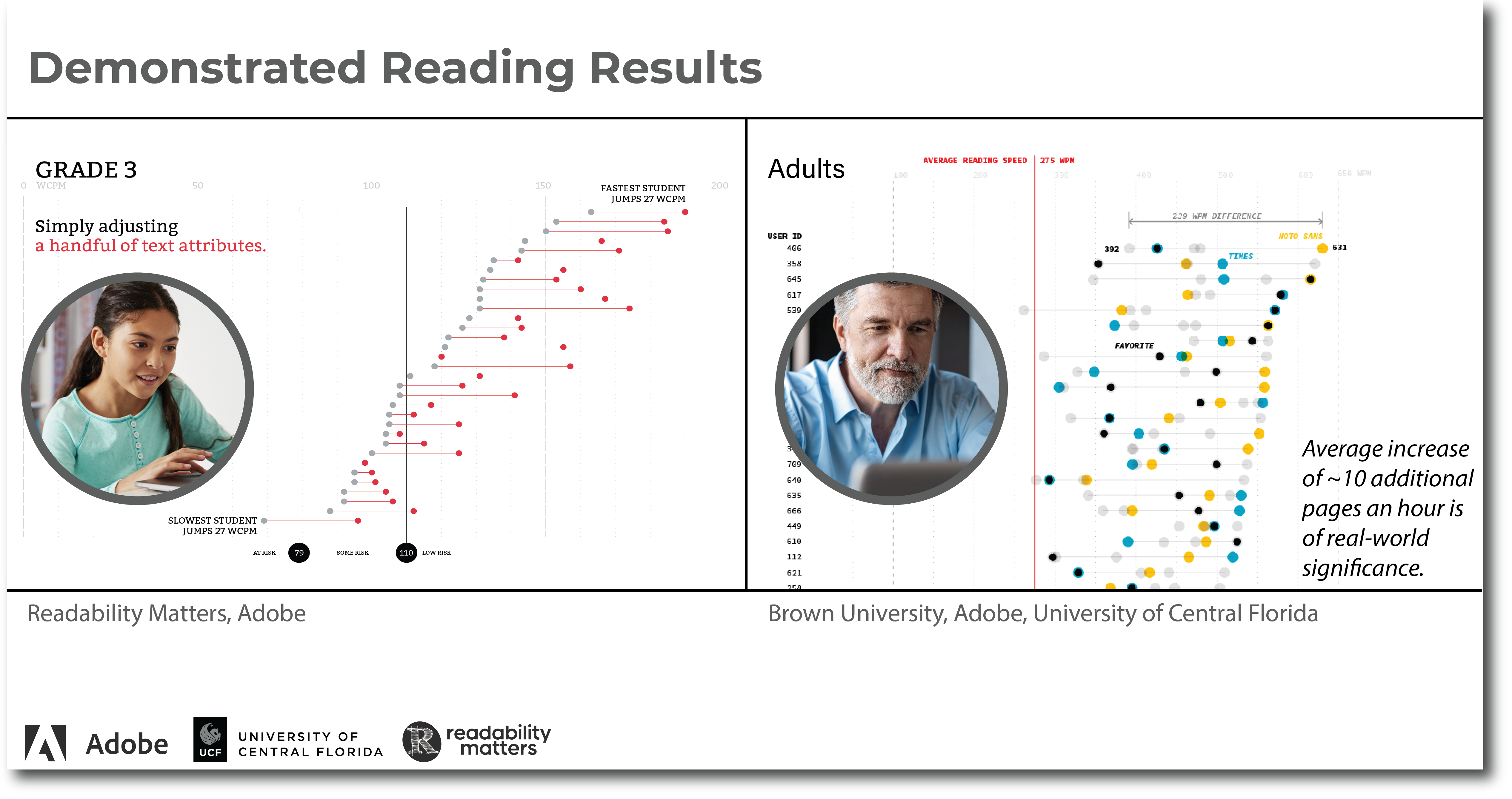

Since early in the 20th century, researchers have documented that individuals respond differently to text format.[4] [5] [6] More recent research has shown that small changes to text format can improve individual reading outcomes. Adults can improve their reading speed by as much as ten pages per hour by changing the font alone.[7] For children, Readability Matters has seen an instantaneous change to reading fluency, the speed of accurate reading, of up to 50% or more. (Advancing the Reading Ecosystem[8]) Personalized reading formats are not just a solution for struggling readers. While a small number of readers did not benefit from a change to the alternative formats offered, both of these studies demonstrate results for individuals of all reading ability levels. In a proof of concept conducted with Adobe, improvements occurred for students reading at the 23rd and 99th percentile of their peers.[9] [10] Strong readers and struggling readers, adults and children, all have the potential to experience improved reading outcomes using a technology-enabled model of reading with personalized text formats.

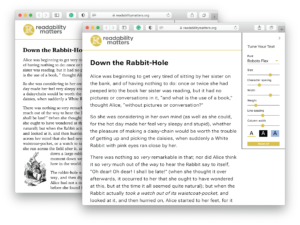

Figure 2: Readers can explore Readability Features in the Readability Sandbox. https://readabilitymatters.org/readabilitysandbox/

Many different audio signals can be adjusted for a better sound experience. In the same way, visual components of text format can be adjusted to create a better reading experience. Text format adjustments include size, shape (base font, character width, and weight), and spacing (inter-character and line spacing). Technology offers new opportunities for you to Tune Your Text[11], improving readability and your reading performance.

An initial set of Readability Features are available on a number of platforms today. (See Readability Hacks: What Can I Do Today? [12]) While these offerings are insufficient to deliver the improved reading outcomes that research demonstrates are possible, tech and publishing companies have begun the work to provide better individual reading experiences.

Given historical publishing file formats, this work is challenging. In order to allow a reader to personalize a text format, the reader must have access to text (not a picture of text as many electronic textbook publishers provide), and the text must be reflowable (it cannot have a character return at the end of every line). Content creators today, in anticipation of electronic distribution on multiple platforms (as with publishing for Amazon), create reflowable text for eBooks. Older content and content for complicated layouts used in technical publications and textbooks are generally not produced as reflowable text.

Further, to the extent that a reader desires Readability Features that exist in one reading app, they are likely to run into conversion and/or digital rights management issues in trying to use content from another providers’ platform.

While the technical challenges are significant, we posit that there is a path to improved reading proficiency through a personalized reading approach.

Christensen’s Disruptive Innovation

In the early 1990s, Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen coined the term “disruptive innovation.” The disruptive innovations “often appear modest at their outset but over time have the potential to transform an industry.”[13] According to the Christensen Institute, “Disruptive Innovations are not breakthrough technologies that make good products better; rather they are innovations that make products and services more accessible and affordable, thereby making them available to a larger population.”[14] (emphasis added)

Christensen’s work on innovation and competitive response is widely considered and applied by technology companies. We believe these models can inform the work required for the next wave of reading technology. Personalized reading formats will expand the electronic reading market to include individuals who have chosen not to (or could not) read with the suboptimal text formats offered today.

With the benefit of 30 years of learnings about disruptive innovation, we are hopeful that tech and publishing companies will join in developing the market-creating performance improvements and resulting social good (in the form of improved literacy) that a move to personalized reading formats promises. Better readers are more confident and have more educational, career, and life opportunities.

The question remains, will the reading application incumbents incorporate the sustaining innovations necessary, or will they leave room for a Christensen-style disruption in content delivery? Who will provide the content delivery platform that best meets the needs of customers working to acquire information? Who will capture the market of new readers? Will new players emerge to offer better reading experiences and win the customers?

Historical Disruption in the Reading Ecosystem

From its inception, written content distribution has experienced significant disruptive and sustaining innovation. It has evolved as it has expanded from documents to books and then to information accessed through digital reading on a myriad of platforms.

Moving from the hand-copying of documents to Gutenberg’s movable type printing press in 1440 was one such disruption. Spencer Nam of The Christensen Institute observed, “Gutenberg’s moveable type printing press was disruptive to handwritten books. Disrupting the manuscript business undoubtedly had its downsides (mostly sentimental), but printing press innovation was overwhelmingly positive for humanity. Gutenberg gave exponentially more people access to more ideas—and at a much lower cost. Initially, printed books weren’t as beautiful as handwritten books, and many manuscript makers lost their jobs, but the printing press industry generated millions of new jobs for the ensuing centuries.”[15] (emphasis added)

In 1971 Michael Hart’s Project Gutenberg[16] was the first provider of free electronic books (eBooks) on mainframe computers. (The project produced only texts with cleared copyrights.) This new technology offered benefits in easy replication, storage, and instant availability; it began to revolutionize the book market.

Another significant disruption process began with the advent of personal computers and their movement from hobbyists to become commercially available in 1977, which eventually created the possibility of distributing digital text to the broad population.

The public release of the world wide web in 1991 and Microsoft Windows in 1992 launched a technology explosion. By the early 2000s, smartphones, tablets, and eReaders were commonplace.

Amazon began selling eBooks and Kindles in 2007–managing digital rights for copyrighted material–and has been termed a disruptor in the reading market. Ryan Marling of the Christensen Institute observed that over the years, Amazon has “upended countless brick and mortar bookstores and other major players in the retail industry.”[17] For customers whose “Job to be Done”[18] was to acquire information or entertainment from a paper book, this is certainly the case.

Today, reading happens on a number of surfaces, across many applications and websites for life, workplace, and educational purposes. The pandemic has been a further accelerator of tech distribution. Students and employees are all the more dependent on technology to accomplish their work. Among students, and especially in high school and post-secondary education, smartphones as reading devices are common.

Today, reading happens on a number of surfaces, across many applications and websites for life, workplace, and educational purposes. The pandemic has been a further accelerator of tech distribution. Students and employees are all the more dependent on technology to accomplish their work. Among students, and especially in high school and post-secondary education, smartphones as reading devices are common.

Sustaining innovation has delivered the capability to enlarge text using many reading applications on these devices, much like paper books are published in large print format. Similarly, some app providers allow readers to change the font, line spacing, or background color of text to support user’s preferences.

Readability Matters asserts that the convergence of increasingly ubiquitous technology, digital content, and reading applications make it possible to imagine a world of personalized reading formats, significantly improving reading proficiency and comprehension.

The Job to Be Done

In their 2016 book discussing innovation and customer choice, Christensen et al. explain, “Customers don’t buy products or services, they “hire” them to do a job. Understanding customers does not drive innovation success, he argues. Understanding customer jobs does.”[19] When accessing and acquiring information is the “Job to Be Done,” the reader may have choices in terms of audio or people willing to share, but most often, reading is a critical competency.

In their 2016 book discussing innovation and customer choice, Christensen et al. explain, “Customers don’t buy products or services, they “hire” them to do a job. Understanding customers does not drive innovation success, he argues. Understanding customer jobs does.”[19] When accessing and acquiring information is the “Job to Be Done,” the reader may have choices in terms of audio or people willing to share, but most often, reading is a critical competency.

The Job to Be Done:

Acquiring Information

Reading proficiency is key to success in education and critical for employee productivity. In these contexts, individuals have huge information processing demands, spending their days interacting with text. Their “Job to Be Done” is to acquire information, which requires reading quickly, accurately, and with deep comprehension. One-format-fits-all reading material will no longer be sufficient when these readers can “hire” competing platforms to offer improved reading experiences.

Beyond performance improvements available to those already participating in the knowledge economy, there is an opportunity to expand participation with resulting tremendous social good. Many in society are essentially non-consumers of written information. We submit that offering improved reading experiences can increase willingness to engage in reading and open new career possibilities.

Better reading is a game-changer for all readers and critical for students and knowledge workers.

The Job to Be Done:

The Job to Be Done:

Learning to Read

The ultimate goal of reading is acquiring information, but the first “Job to Be Done” is to learn to read. A significant number of children struggle with this task, with great risk of less academic success than their cognitive abilities would predict.

The current educational system is designed assuming a child will master reading skill by the 3rd grade. The Children’s Reading Foundation asserts, “Academically, children who are not reading on grade level by the end of third grade struggle in every class, year after year, because over 85 percent of the curriculum is taught by reading. Reading is the skill by which students get information from books, computers, worksheets and boards to learn math, science, literature, social studies and more.”[20] Further, reading expert Dr. Sally Shaywitz notes, “Once a child falls behind, he must make up thousands of unread words to catch up to his peers who are continuing to move ahead. Equally important, once a pattern of reading failure sets in, many children become defeated, lose interest in reading, and develop what often evolves into a lifelong loss of their own sense of self-worth.”[21] Psychology researchers, Hebbecker et al., found a reciprocal relationship between reading skill and reading motivation, perhaps explaining the increase in engagement we have seen with students using personalized text formats.[22]

Dr. Susanne Nobles, Chief Academic Officer of ReadWorks, notes that a student’s issue with the physical mechanics of reading is rarely considered and can be hard to identify. “Students wrongly assume that the problem is with them. With format changes, they can successfully access the meaning of the written words.”[23] The problem is not the reader; it is the reading material.

As noted in the introduction, research demonstrates that using a personalized text format can have an instantaneous positive impact on a child’s reading fluency[24] (speed of accurate reading). Better text formats do not replace good phonics or reading strategy instruction. Rather, they can expose the teaching that the child previously received. With more optimally formatted material, the child immediately accesses the skills and exhibits more fluency. Reading to understand is a complex skill that requires the use of several cognitive processes simultaneously. Fluency improvements may reduce the extraneous load on the reader’s cognitive processing. When the decoding and word recognition components of reading require less effort, the result is to free up working memory for comprehension-related tasks.[25]

Readability Matters asserts that impacting reading success at an early age is critical. Creating strong readers at a young age has the potential to reduce the number of adult non-readers over time. Becoming a good reader impacts interest and engagement in learning through the school years. Better reading capability can change an educational trajectory as a child becomes more willing to engage in learning. The ability to read is a predictor of confidence and self-esteem. It influences friend and education track choices, which impact professional pursuits, income, and life experience.[26]

Readability Matters asserts that impacting reading success at an early age is critical. Creating strong readers at a young age has the potential to reduce the number of adult non-readers over time. Becoming a good reader impacts interest and engagement in learning through the school years. Better reading capability can change an educational trajectory as a child becomes more willing to engage in learning. The ability to read is a predictor of confidence and self-esteem. It influences friend and education track choices, which impact professional pursuits, income, and life experience.[26]

While there is much focus on children learning to read, the above is also true for adults working to master reading skills. The National Assessment of Adult Literacy found that only 15% of adults in the US are proficient readers.[27] In 2020, the Barbara Bush Foundation estimated that “low levels of adult literacy could be costing the US as much as $2.2 Trillion per year.” They correlated adult literacy “with important outcomes such as personal income, employment levels, health, and overall economic growth.” [28]

The New Market:

Demand for Performance Improved Reading

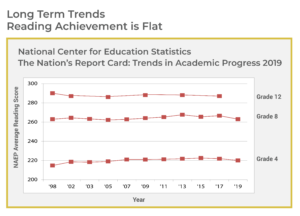

Reading scores have been essentially flat since 1998 when the US Department of Education began tracking them.[29] Increasing readability by personalizing typographic features for the individual produces improved reading outcomes and can change the trajectory of performance improvement. Once the value of personalization is understood, demand will increase rapidly and has the potential to shift these reading scores.

Readers have accepted one-format-fits-all reading material, not recognizing the potential for better reading experiences and associated performance gains. One could argue that the demand for reading performance improvement in the mainstream market has been non-existent.

Adding Readability Features to existing platforms could be seen as sustaining innovations. And they may be for current reading customers. But when competing against the status quo and current non-consumption, there is an opportunity for new market disruption[30], bringing more readers into the market. Christensen et al. noted, “New market disruptions take hold in a completely new value network and appeal to customers who have previously gone without the product.”[31] Readability Matters calls for the current market leaders, charging for content but already offering free reading platforms, to engage in innovation to deliver improved reading, a virtuous solution to low literacy.

We submit that the incumbents have already begun the innovation process, even if they do not fully understand the potential for market expansion and the social good they are creating. (See Readability Hacks: What Can I Do Today? [32]) They offer low-cost (free) solutions with good enough functionality for the underserved portion of the population (the ~70% of us that could be better at reading) to benefit. The Readability Features added as sustaining innovations can be used today. (Some readers gain reading speed and accuracy by simply changing the font or character size.)

The important question is, can current reading application providers produce the breakthrough innovations required in terms of additional features, reader profiles, optimal format determination tools, and interoperability standards? If not, how will we fund solutions that need to compete with the incumbent’s free readers and solve the digital rights management issues created by moving content from their platforms to a better reading platform?

As an example, Christensen described that Southwest Airlines “rapidly stole market share from established carriers while also bringing new customers to air travel.[33] We believe that the provider offering better reading experiences will satisfy existing customers’ future demand for improved reading performance. Likewise, the provider will find an underserved market of reading material customers and grow their sales.

Personalized reading formats are the next wave in reading technology; they have the potential to attract non-consumers to reading products because of the improved reading experience.

New Data, New Categories, New Insights:

A Research-Informed Approach

Evidence of impact should cause researchers to look at data differently. The historical propensity to optimize reading formats for the population rather than for individuals generates data that will not produce the required insights.

Christensen asserts that,

“In order for our scientific understanding of the world to progress, we must continually crawl inside companies, communities, and the lives of individuals to create new data in new categories that reveal new insights… Big data also tends to gloss over or ignore anomalies unless it’s crafted carefully to surface these to humans. That is, big data tends to be far more focused on correlation rather than causation and as such ignores examples where something doesn’t follow what tends to happen on average. It’s only by exploring anomalies that we can develop a deeper understanding of causation.”[34]

Since early in the 20th century, researchers looked for the best font, character spacing, or line spacing for the population at large to support the best possible one-format-fits-all model. Because of the paper distribution model, typographers were limited to this approach. Consistent with Readability Matters’ findings, independent research demonstrates the importance of personalization. In 2020, Wallace et al. proved that adult readers respond significantly differently to a simple change. They documented reading performance gains of as much as ten pages per hour with a change in font alone.[35] In looking for the best text format for the population, earlier research missed the potential performance gains available when these settings are personalized for the individual. Large data sets focused on evaluating the variability in the needs of each reader are required.

Since early in the 20th century, researchers looked for the best font, character spacing, or line spacing for the population at large to support the best possible one-format-fits-all model. Because of the paper distribution model, typographers were limited to this approach. Consistent with Readability Matters’ findings, independent research demonstrates the importance of personalization. In 2020, Wallace et al. proved that adult readers respond significantly differently to a simple change. They documented reading performance gains of as much as ten pages per hour with a change in font alone.[35] In looking for the best text format for the population, earlier research missed the potential performance gains available when these settings are personalized for the individual. Large data sets focused on evaluating the variability in the needs of each reader are required.

An interdisciplinary research collaboration has formed–spanning cognitive science, visual science, human-computer interaction, education, and typography, from industry and academia–to study and inform better readability.[36] The scope of research is broad, and the methods span ages, platforms, and assessment tools. Studies are evaluating the impact of Readability Feature changes on reading speed with comprehension held constant. Others are looking at the impact of changing character anatomy through font change compared to only changing typographic features (character width, spacing, weight, etc.) Additional work is specifically evaluating changes to comprehension through word- and passage-level tasks.[37] Research tools and data are shared publicly in order to facilitate the rapid expansion of research results to inform personalized reading implementations.

Transition to a model of personalized reading begins with the subset of required features available in a number of applications today and a clear need for new research-informed features, testing, and delivery tools. Modern readability research must identify the most impactful format changes to improve reading speed, accuracy, and comprehension. This research is necessary to support innovation that will deliver not just incremental gains but significant performance improvements.

The Next Wave of Innovation

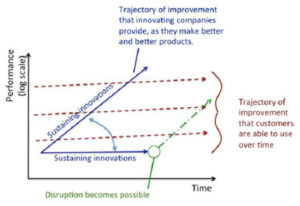

Figure 4: Note: From “Fresh Insights From Clayton Christensen on Disruptive Innovation.” By S. Denning, (2015) Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2015/12/02/fresh-insights-from-clayton-christensen-on-disruptive-innovation/

Readability Matters submits that reading application performance could (should) be measured by the potential for the app to personalize text format and increase the reader’s proficiency.

Referencing Christiansen’s model of disruption (see Figure 1), the sustaining innovations offered by reading apps today fall below the trajectory of improvement that customers are able to use. Because the application is not enabling reader performance to increase, the reader experiences a flat curve of performance improvement from the app, creating the opportunity for a disruptive entrant.

Bower and Christensen note, “The technological changes that damage established companies are usually not radically new or difficult from a technological point of view.”[38] There are a handful of these simple to deploy Readability Features in existing content delivery platforms. The existing features are used by savvy readers today to improve their reading experiences. (For example, in many apps, individuals can change font or text size to read more effectively.)

Expanding on existing infrastructure is the most cost-efficient way to deliver higher reading performance at scale because of the previous investments. Reading applications and platforms should be modified to utilize reflowable text, solve digital rights management issues, offer additional Readability Features, and create the ability to store reader profiles.

To realize the full impact of personalized reading, additional sustaining innovation is required. Will content providers innovate to increase reader proficiency? Will they leave performance flat, leaving an opportunity for a disruptive entrant?

Big Tech Moves Towards Disruption:

Adobe’s New Liquid Mode with Reading Settings

In order to reformat it, the text must be reflowable. In 2020, Adobe announced their new Liquid Mode functionality for the free Adobe Reader. This technology uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to reverse-engineer a fixed-format PDF, making the text reflowable and improving reading experiences on mobile devices.[39]

With Liquid Mode, Adobe added Reading Settings, an important first step in making personalized reading experiences possible for their readers. They disclosed results from a Readability Matters test of their Reader prototype. Significant reading fluency gains were achieved using a variety of text modifications. [40] [41] (The new version of Adobe Reader is available on mobile platforms and Playstore-compatible Chromebooks.) The released Reading Settings offer the reader the option to change text size and expand or contract character spacing and line spacing. Adobe’s Rick Treitman explained that three of the five features tested had been deployed to date, with more exciting work underway.[42] Importantly, Adobe is the first reading application provider to offer the reader granular control of character spacing.

In 2019, Adobe Research Scientist Zoya Bylinskii and collaborators began studying readability in adult readers.[43] Adobe later announced their investment in further readability research, funding the Virtual Readability Lab under the direction of Dr. Ben D. Sawyer at the University of Central Florida[44] to support the research-informed implementation of Readability Features in their products.

Adobe has launched a Corporate Social Responsibility initiative, “Reimagining reading to better fit each reader.”[45] They are working with educators, experts, nonprofits, and technologists to personalize the experience of reading on digital devices and help people of all ages and abilities read better. This catalytic innovation has social change as its primary objective.

The Next Gutenberg Press

The authors submit that, as Christensen and colleagues describe, readers are stuck in a model of suboptimal status quo and a resulting set of non-consumers in the written content market. We can imagine a world where reading content is AI-enabled to adjust automatically to deliver each reader’s optimal experience.

In the meantime, there is research to complete and development to be done. Additional features must be added to the applications used for reading. Testing tools empowered with artificial intelligence and machine learning must be developed to ensure apps are properly configured to create optimal outcomes. Standards must be defined to allow interoperability between applications. User profile creation must be added to make personalized reading formats possible in an educational setting. And, in the context of educational and business use, the implementations must be simple, low-cost, and efficient to deploy.

Customers will choose providers that offer personalizable reading content; the providers that do not will lose sales.

The next generation of reading will be dominated by the reading applications that innovate to deliver the best reading experiences. Will it be the current content providers who innovate or a new disruptive reading application that leads?

Gutenberg disrupted the scribes. Amazon disrupted book stores. Who will win in the personalized reading market?

Join Us

Join us in giving exponentially more people access to more ideas. Help us create the next Gutenberg press for reading.

The tech-for-good nonprofit Readability Matters is building an ecosystem of partners, investors, developers, researchers, marketers, early adopters, and more… In short, we are looking for the network of thinkers and doers that will collaborate to deliver personalized reading environments, empowering everyone everywhere to achieve more.

ReadabilityMatters.org

About Readability Matters

The tech-for-good nonprofit Readability Matters was formed in 2019 but was 15 years in the making. Founders Kathy Crowley and Marjorie Jordan had seen the use of alternate text formats help dyslexic readers in 2004. With emerging technology, they could see the potential to implement personalized reading formats at scale. The founders posited that small changes to text format would improve reading outcomes for most readers.

In 2015, they set out to learn just how broad the impact might be, testing an entire classroom of students. In fact, a simple change from a textbook format to the clean round font, AvantGarde, improved reading fluency for 55% of the students. Another 40% read best using AvantGarde with additional character spacing, character expansion, or both.

By 2015 tech companies had begun delivering users the capability to change font and character size on smartphones and tablets. Marjorie theorized that with additional features, digital text could be optimized for individuals creating unlimted possibility for adjustment and scale of personalized text formats. Additionally, she proposed that reader profiles could manage students’ individual text settings, critical for education usage.

In 2018, using a standard iPad font, Avenir, as a base font, the test was repeated. Again, readers of all levels showed reading improvements using text modifications delivered by formats created using Readability Features in a prototype version of Adobe Reader. The theory was proven; reading outcomes could be improved with small changes to text format delivered with digital text and readability features.

Readability Matters was formed to share insights with tech and publishing companies. Readability Matters continues the commitment to research-informed implementations; they partner with an extensive interdisciplinary collaboration of researchers from universities and industry.

Readability Matters works to build better reading, empowering everyone everywhere to achieve more.

Be the best reader you can be.

Figures

Figure 1: What is Readability, and Does it Matter? (2021, February 16). Readability Matters. https://readabilitymatters.org/articles/what-is-readability-and-does-it-matter

Figure 2: Readability Matters’ Readability Demo Sandbox: https://readabilitymatters.org/readabilitysandbox/

Figure 3: Using Readability Features to Impact Education. (n.d.). Readability Matters. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from https://readabilitymatters.org/education

Figure 4: Denning, S. (2015, December 2). Fresh Insights From Clayton Christensen On Disruptive Innovation. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2015/12/02/fresh-insights-from-clayton-christensen-on-disruptive-innovation/

Notes

[1] National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). (n.d.). National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved January 20, 2021, from https://nces.ed.gov/naal/kf_demographics.asp#3

[2] National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Report Cards. (2019). https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/

[3] Vaca, R. T., Vaca, J. A. L., & Mraz, M. (2013). Content Area Reading: Literacy and Learning Across the Curriculum (11th Edition). Pearson.

[4] Tinker, M. A., & Paterson, D. G. (1928). Influence of type form on speed of reading. Journal of Applied Psychology, 12(4), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0073699

[5] Erdmann, R. L., & Neal, A. S. (1968). Word legibility as a function of letter legibility, with word size, word familiarity, and resolution as parameters. Journal of Applied Psychology, 52(5), 403-409. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0026189.

[6] Sandra Wright Sutherland (1989) The Forgotten Research of Miles Albert Tinker, Journal of Visual Literacy, 9:1, 10-25, DOI: 10.1080/23796529.1989.11674437

[7] Wallace, S., Treitman, R., Huang, J., Sawyer, B. D., & Bylinskii, Z. (2020). Accelerating Adult Readers with Typeface: A Study of Individual Preferences and Effectiveness. Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1145/3334480.3382985

[8] Crowley, K., & Jordan, M. (2019). Advancing the Reading Ecosystem Toward a Future of Personalized Reading: Human Factors Research + IT Systems Promise Value for Education, Business and Individuals. https://readabilitymatters.org/advancing-reading

[9] Crowley, K., & Jordan, M. (2019). Tech Proof of Concept Results Summary. https://readabilitymatters.org/results-summary

[10] Crowley, K., & Jordan, M. (2020, October 22). The Adobe Tech Proof of Concept, Part II. Readability Matters. https://readabilitymatters.org/articles/the-tech-proof-of-concept-part-ii

[11] Tune Your Text. (2020, June 26). Readability Matters. https://readabilitymatters.org/articles/tune-your-text

[12] Readability Hacks to Improve Readability for All. (n.d.). Readability Matters. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://readabilitymatters.org/readability-hacks

[13] Dillon, K. (2020, February 4). Disruption 2020: An Interview With Clayton M. Christensen. MIT Sloan Management Review. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/an-interview-with-clayton-m-christensen/

[14] Disruptive Innovations. (n.d.). Christensen Institute. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from https://www.christenseninstitute.org/disruptive-innovations/

[15] Nam, S. (2015, March 13). Health care needs its Gutenberg press. Christensen Institute. https://www.christenseninstitute.org/blog/health-care-needs-its-gutenberg-press/

[16] Project Gutenberg. (n.d.). Project Gutenberg. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from https://www.gutenberg.org/

[17] Marling, R. (2017, June 12). Could Amazon deliver your next prescription? Christensen Institute. https://www.christenseninstitute.org/blog/amazon-deliver-prescription/

[18] Dillon, K. (2020, February 4). Disruption 2020: An Interview With Clayton M. Christensen. MIT Sloan Management Review. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/an-interview-with-clayton-m-christensen/

[19] Christensen, C. M., Dillon, K., Hall, T., & Duncan, D. S. (2016). Competing Against Luck: The Story of Innovation and Customer Choice (1st edition). Harper Business.

[20] What’s the Impact. (n.d.). The Children’s Reading Foundation. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from http://www.readingfoundation.org/the-impact

[21] Shaywitz, M.D., S., & Shaywitz, M.D., J. (2020). Overcoming Dyslexia, A New and Complete Science-Based Program for Reading Problems at Any Level (Second Edition). Vintage Books, A Division of Random House, Inc.

[22] Hebbecker, K., Förster, N., & Souvignier, E. (2019). Reciprocal Effects between Reading Achievement and Intrinsic and Extrinsic Reading Motivation. Scientific Studies of Reading, 23, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2019.1598413

[23] Nobles, Ph.D., S. (2020, November 19). Interview with Dr. Susanne Nobles [Readability in Education].

[24] Fluency: Introduction. (2014, March 17). Reading Rockets. https://www.readingrockets.org/teaching/reading101-course/modules/fluency-introduction

[25] Crowley-Sullivan, M. (2020, July 16). Increase Readability, Reduce Cognitive Load. Readability Matters. https://readabilitymatters.org/articles/increase-readability-reduce-cognitive-load

[26] Ritchie, S. J., & Bates, T. C. (2013). Enduring Links From Childhood Mathematics and Reading Achievement to Adult Socioeconomic Status. Psychological Science, 24(7), 1301–1308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612466268

[27] National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). (n.d.). National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved January 20, 2021, from https://nces.ed.gov/naal/kf_demographics.asp#3

[28] Nietzel, M. T. (2020, September 9). Low Literacy Levels Among U.S. Adults Could Be Costing The Economy $2.2 Trillion A Year. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaeltnietzel/2020/09/09/low-literacy-levels-among-us-adults-could-be-costing-the-economy-22-trillion-a-year/

[29] National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Report Cards. (2019). https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/

[30] Christensen, C. (2008). Disruptive Innovation and Catalytic Change in Higher Education. Forum Futures.

[31] Christensen, C. M., Raynor, M. E., & McDonald, R. (2015, December 1). What Is Disruptive Innovation? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation

[32] Readability Hacks to Improve Readability for All. (n.d.). Readability Matters. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://readabilitymatters.org/readability-hacks

[33] Christensen, C. M. (2006, December 1). Disruptive Innovation for Social Change. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2006/12/disruptive-innovation-for-social-change

[34] Dillon, K. (2020, February 4). Disruption 2020: An Interview With Clayton M. Christensen. MIT Sloan Management Review. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/an-interview-with-clayton-m-christensen/

[35] Wallace, S., Treitman, R., Huang, J., Sawyer, B. D., & Bylinskii, Z. (2020). Accelerating Adult Readers with Typeface: A Study of Individual Preferences and Effectiveness. Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1145/3334480.3382985

[36] A Collaborative Interdisciplinary Readability Research Approach. (2021, March 20). Readability Matters. https://readabilitymatters.org/articles/a-collaborative-interdisciplinary-readability-research-approach

[37] K-8 Student Readability Research Announced. (2020, October 19). Readability Matters. https://readabilitymatters.org/articles/chapman-university-k-8-student-readability-research-announced

[38] Bower, J. L., & Christensen, C. M. (1995). Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave. Harvard Business Review, January-February 1995. https://hbr.org/1995/01/disruptive-technologies-catching-the-wave

[39] Still, A. (2020, September 23). Adobe unveils ambitious multi-year vision for PDF: Introduces Liquid Mode. Adobe Blog. https://blog.adobe.com/en/publish/2020/09/23/adobe-unveils-ambitious-multi-year-vision-for-pdf-introduces-liquid-mode.html

[40] Crowley, K., & Jordan, M. (2019). Tech Proof of Concept Results Summary. https://readabilitymatters.org/results-summary

[41] Crowley, K., & Jordan, M. (2020, October 22). The Adobe Tech Proof of Concept, Part II. Readability Matters. https://readabilitymatters.org/articles/the-tech-proof-of-concept-part-ii

[42] Treitman, R., Sawyer, B. D., & Rodrigo, S. (2020, October 20). This Changes Everything: New Approaches to Reading. https://www.adobe.com/max/2020/sessions/this-changes-everything-new-approaches-to-reading-s6826.html

[43] A Collaborative Interdisciplinary Readability Research Approach. (2021, March 20). Readability Matters. https://readabilitymatters.org/articles/a-collaborative-interdisciplinary-readability-research-approach

[44] Sharma, M. (2020, October 20). Democratizing digital literacy: Adobe unveils readability research partnerships at MAX. Adobe Blog. https://blog.adobe.com/en/publish/2020/10/20/democratizing-digital-literacy-readability-research-unveiled-at-max.html

[45] Readability initiative. (n.d.). Adobe. Retrieved March 3, 2021, from https://www.adobe.com/about-adobe/corporate-responsibility/readability.html

© Copyright 2021 Readability Matters, version 1.1.